In 2007, SL Bhyrappa’s novel Avarana was published in Kannada, immediately creating a huge wave and becoming a significant turning point in Kannada literature. While it was never expected to have a national impact, it did over many years, much later. To understand the impact of Avarana, we need to step into the literary history of Karnataka.

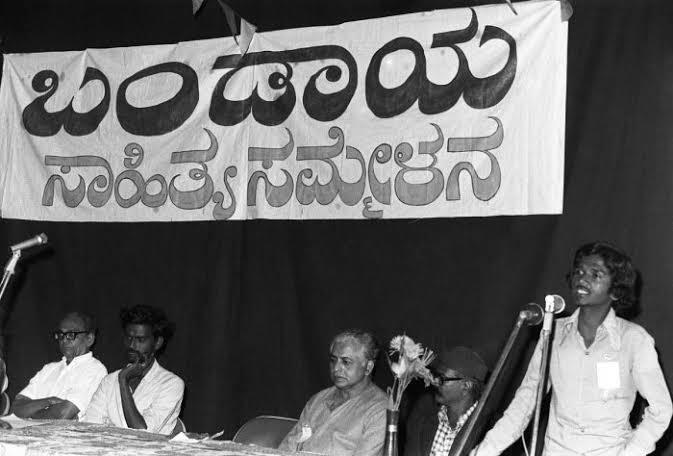

From 1880-1960, the literary movement in Karnataka was Navodaya, which was culturally rooted. The next literary movement was Navya, which lasted from 1960-1980 and was modern with Western influence. The literary movement from 1970-2000 was Left Wing, Bandaya & Dalit, which was both literary and political, known as the Rebellion. Navodaya never died and continued to flow like River Saraswati, with its impact on society being the greatest. However, it simply did not have as many stalwarts as it did in the 1880-1960 period. SL Bhyrappa cannot be considered as Navodaya, but he took on their legacy in a different direction.

The Navya period brought many talented writers who were mostly looking at the West for influence in expression and culture, seeking to blend that into Tradition/History, even reinterpreting it, and moving towards Lohia+Secularism. Even they could not abandon Navodaya. Girish Karnad and UR Anantmurthy emerged in this scenario. Karnad’s first play “Maa Nishaada” came in 1958, Yayati in 1961 and Tughlaq in 1964. UR Anantamurthy began writing short stories in the late 50s, and his world-famous “Samskara” came in 1965. SL Bhyrappa began to write at the same time. From 1970 onwards, another significant writer emerged, P Lankesh, father of Gowri Lankesh. A great writer and successful journalist, he was a mix of Navya, Left, Bandaya, Lohia, and Secularism. He borrowed least from Navodaya but did not disrespect it and sought to appropriate it into his view.

Even in this period, the books that sold more on the ground were all a continuation of the Navodaya Tradition. SL Bhyrappa and Poornachandra Tejaswi(Son of Kuvempu), the latter in spite of his non-Navodaya character politically, wrote in the absolutely Navodaya tradition in his works. However, institutional power began to move towards the Left and Secularism all over the country, thanks to Indira Gandhi. The 70s was a period of enormous creativity that catapulted them into immense institutional power in the 80s and 90s. In this midst, SL Bhyrappa stood on the contrary.

As the cultural battle continued, the Left and secular forces continued to dominate the institutions, including the media and academia. They were able to influence the narrative and shape the discourse in their favor.

But despite their efforts, SL Bhayrappa’s novels continued to sell well and gain popularity among the people. His writings challenged the dominant narrative and offered a different perspective on Indian history and culture. One of his most controversial novels, Avarana, was published in 2007 and caused a great stir in the literary world. It exposed the distortion of Indian history and the manipulation of the narrative by the Left and secular forces. Despite the popularity of his writings, SL Bhyrappa faced constant criticism and ridicule from his opponents. P Lankesh was really at the forefront of this. A greatly talented man, as a journalist he could be such a terror. He trolled and humiliated people that he did not agree with and nobody could do anything. Net summary is that they managed to subdue the Navodaya continuation.

The stalwart among writers who withstood this cultural assault was SL Bhyrappa. There were others but he was the greatest. He not only continued to write on the contrary, all of them sold well and translated.

The cultural battle that started in the 80s and 90s continues to this day, with different forces vying for control of the narrative and the discourse. The Left and secular forces still dominate the institutions, but the society is no longer willing to be passive observers. People are beginning to question the dominant narrative and seek alternative voices and perspectives. The emergence of social media and alternative media outlets has also provided a platform for different voices and challenged the monopoly of the mainstream media. The cultural battle that started in the 80s and 90s has had a profound impact on the Indian society and its cultural and intellectual landscape. It has exposed the fault lines and divisions in the society and highlighted the need for a more open and inclusive discourse that allows for different voices and perspectives.

The literary scene in Karnataka during the 90s was marked by a special conflict or competition between two prominent writers, U.R. Ananthamurthy and S.L. Bhyrappa. This was fueled by constant comparisons between their works, particularly UR Anantamurthy’s “Samskara” and Bhyrappa’s “Vamsha Vriksha”. However, it was Girish Karnad who later joined the fray, shaping and acting in “Samskara” and directing adaptations of both “Vamsha Vriksha” and another SLB novel, “Tabbaliyu Neenade Magane”.

The competition between UR Anantmurthy and Bhyrappa reached new heights when UR Anantmurthy was honored with the Jnanapeetha Award in 1994, followed by Karnad in 1998. This led to a sense of superiority among the writers, with Karnad continuing to produce controversial works like “Dreams of Tipu Sultan” and “Agni Mattu Male (Fire and Rain)”, which manipulated history and tradition. He followed these up with “The Battle of Rakkasatangadi”, another controversial work which is a epic of downfall of Vijayanagara empire an battle between Aliya Ramarajya and Bahamanis.

Meanwhile, UR Anantmurthy continued to anchor cultural secularism and shifted towards left secularism post-2004. Bhyrappa, on the other hand, wrote three outstanding novels during this time: “Saartha” (1998), “Mandra” (2001), and “Avarana” (2007). “Saartha” set the stage for a battle as it painted a picture of the past that was completely against the Lohia Secularism Left Modern penchant, showcasing the problems of Buddhists and unabashedly painting the Turk assault while positioning Adi Shankaracharya differently. While others could not criticise Saartha much – for it was absolutely brilliantly written (better than Avarana while citing primary sources with it). But P Lankesh was made of different material. He ran a vitriol against Bhyrappa for weeks together. Can be found in the pages of Lankesh Patrike in 1998-99.

Interestingly, In 2006, BJP came to power in Karnataka, DH Shankaramurthy made a statement that “Tipu was anti-Kannada,” which sparked a debate on the real face of Tipu Sultan. This debate continued for two months in various magazines and newspapers. The criticising segment was obviously aggressive, while those who supported Shankaramurthy wrote cautiously.

This debate was a turning point in Indian literature and society. SD Sharma’s Hindi book on Tipu Sultan was already translated into Kannada, and certain aspects of Tipu, not known in the 80s, had emerged. SL Bhyrappa, a renowned Kannada novelist, wrote a long piece presenting Tipu’s real face, based on SD Sharma’s book and other references. He criticised Girish Karnad’s play on Tipu Sultan, which was published in two full centre pages over two days.

Girish Karnad, known for his suave and sophisticated image, lost his mind completely and responded with personal, abusive, crying, and shouting comments. This made it very clear that Karnad, Chandrashekhar Kambhar, and others were all hollow inside in terms of substance and were only brilliant in their literary talent. Criticism from the tradition that was cautious until then became bold after this.

Avarana, Bhyrappa’s novel, was the final turning point. When Avarana was released, Kambhar had just released his novel and was getting criticised for multiple things. Avarana was just a massive tsunami from day one, and the left liberal Lohia Secularism segment was in shock. Bhyrappa had for the first time shifted the lens on the Abrahamic present and its problems and showed it as a continuation of the Abrahamic past.

UR Anantmurthy chose to lead from the front and criticised SL Bhyrappa in a speech as a mere debater and so on. Most newspapers were still with the left, but Vijaya Karnataka had emerged under Vishweshwar Bhat, who made a fantastic innovation. He invited SMS responses to UR Anantmurthy’s speech and published them without editing in the centre page. People poured their anger on UR Anantamurthy in ways that he never recovered from.

Avarana broke a psychological barrier and demonstrated that one could be confidently truthful about civilizational narratives, especially the conflict with the Abrahamic past and present. After this, in the mainstream, people began to very confidently write about all aspects of history and culture. The success of Avarana demonstrated that one could write from the tradition’s side with confidence, and many more people began to do so.

The novel was an absolute “raNa” in Kannada, intense, and a significant artistic achievement as it could pack a present and complex history into an artistic complex full of literary metaphors. It played a crucial role as it was both artistic and activistic. While there were others like Baragur Ramachandrappa who would continue many things of the Navya Left Lohia dimensions, the voice lost its intensity and the teeth its sharpness.

Overall, SL Bhyrappa’s Avarana had a significant impact on Indian literature and society, breaking a psychological barrier and encouraging people to confidently write about all aspects of history and culture.

(I have attempted to express, grab and knot my understanding of what I have heard, seen, and read, with most of the information coming from sources like Twitter, newspaper articles, and lectures. While these are not my own opinions, I appreciate the connections being made and I find myself in agreement with them.)